🇬🇧 I’ve wanted to write this article for a few months now, ever since I’ve finished the book I’m going to write about here. Mind you, this is not a book review in the least, but personal observations of how I perceived it and how some things are so very different for modern kendoka.

I’ve received this book last year, I believe, from a kendo friend from another city. I didn’t even know it existed, not to mention that it was translated, as there aren’t any other kendo books to my knowledge that are translated into Romanian. But with the huge help of Tsushima-sensei (the one who has brought kendo in Romania) we now have this book available here. Which is fantastic!

The Romanian title is “From Pilot on a Fighter Plane to Police Investigator”. The book gathers the memories of О̄dachi Kazuo, a former fighter in World War II for the Japanese troops. He fought in the Special Attacks Division – the exact pilots that flew planes with the bomb tied to the plane to crash into the enemy. And despite being in 7 operations of the Special Attacks, he lived to tell his story so many years later (even if for tens of years he hasn’t told anyone his part in the war because of how the surviving fighters were seen when they returned in Japan).

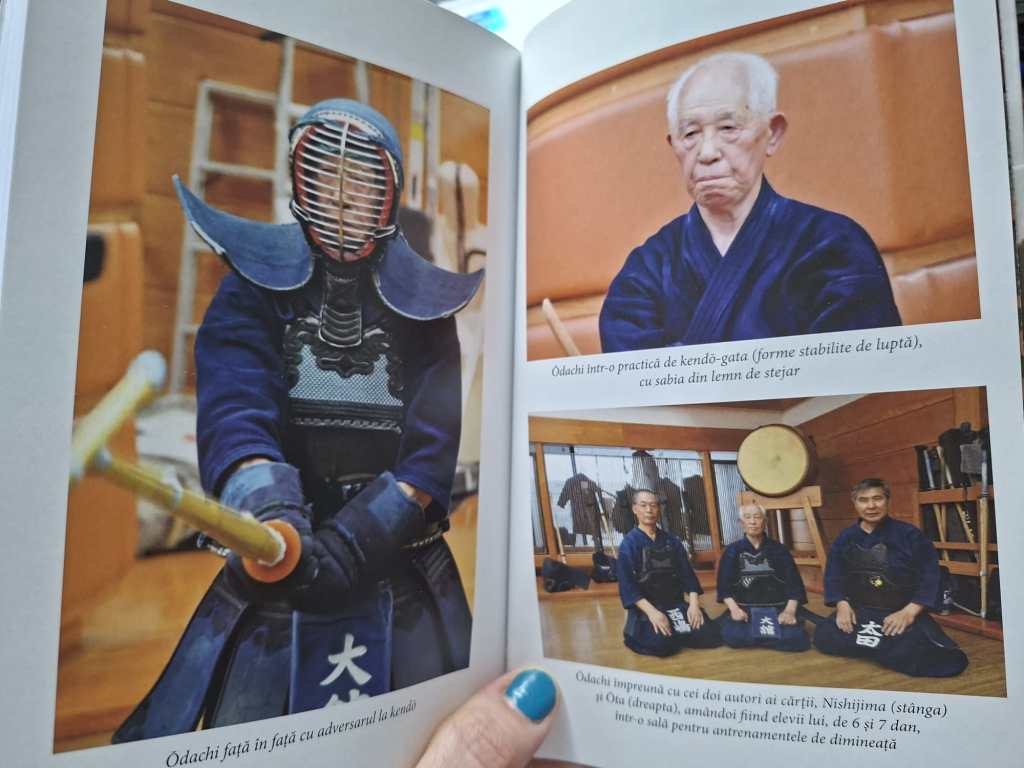

The book is written in first person as О̄dachi sensei recounts mainly his war memories, with additional notes from the two authors who have put the book together: Nishijima sensei and О̄ta sensei. But what I want to talk about is the bits of kendo he mentioned and how we bring these bits into our training.

I have always wondered how those Japanese boys and men had the courage to fight the way they did back in WWII (kamikaze is a coined term now, isn’t it?) and their loyalty for the country. After reading this book, an actual first-hand (!!) recount of how things were, I realized that it was the sheer willpower and “insanity” that they managed what they did. The planes were not too fast, the conditions were far from ideal, and the so-praised Japanese order kind of lacked (contradicting or confusing orders etc.)

But all this is beside the point of the article.

О̄dachi sensei’s family was descendant of the Nitta clan, a direct descendant of Seiwa Genji (for more information, I guess the internet will help. For me, these are just names, but suffice to say they are important and well known in Japanese history). He was born on December 11th 1926, in Kitano, Kotesashi village, Iruma sector (today is the city of Tokorozawa, Saitama prefecture). He started kendo at the age of 11, which was considered rather late. His sensei was 23 y.o. Kuroda Seiji sensei. Kuroda sensei practiced hokushin ittо̄ ryū (old style of kenjutsu founded in the last part of Edo period – 1820 – by Chiba Shusaku Narimasa, who was one of the kensei masters). Not only to О̄dachi sensei, but to the other kids’ eyes as well, Kuroda sensei resembled a samurai from old times. His trainings were very harsh and were “old school” trainings. Something that I believe it’s being avoided today (modern kids, modern teaching techniques, I guess).

At that time, kendo was so close to the samurai time that they still had ashibarai (kicking, apparently used mostly for defending) and kumiuchi (if the fighter lost his sword, he was allowed to continue the fight in hand-to-hand combat). As we kendo practitioners know, these are now forbidden. If I am not mistaken, ashibarai is still used in Tokuren (special police in Japan) trainings as part of the arresting techniques curriculum and it’s still used in the Tokuren championships. I know that I have seen some youtube videos with kendo matches showing this technique (see here a reference. Maeda-senshu does ashibarai to Tanaka-senshu at the final of 2018 All Japan Police Team Champs Final, Osaka vs. Kanagawa).

You can only imagine how much it hurt for a 11 y.o. to receive leg kicks. О̄dachi sensei mentions this, saying the pain was unbearable. However, he reckons that it helped him strengthen his hips because he was trying hard not to fall. And sure enough, after a while, he didn’t fall anymore. Now, let’s bear in mind that this was in 1937. What matresses, what soft wooden floor? They were doing kendo barefooted on the ground, outside the school.

Scratches on elbows and knees? Check!

Earth and sand on the cuts? Check!

Blood caked on the wounds? Check!

Later, they used the ceremony hall for the trainings, but the trainings weren’t easier. It was the same intensity, if not harder, as the kids grew up.

One interesting thing was that he mentioned his mother telling him to give up kendo because she couldn’t stand seeing him hurt like this. A mother will always be a mother, despite the times.

I don’t want to mention all the bits that shocked me in the book (how confused and unorganized was the Japanese army, especially towards the end of the war). One thing that impressed me and triggered deeper thoughts was how О̄dachi sensei said he had to pay attention during the attack flights. This is WWII, remember? So the technology wasn’t as good as it is today. Moreover, the Japanese planes weren’t the pinnacle of technology, either. He had to stay focused for at least half an hour at a time, if not even more, in all directions. Literally, all directions: front, rear, left, right, up, and down. The enemy could come from anywhere, at anytime. Not paying attention meant certain death.

Can you imagine that?

Now bring this idea into a kendo match. Instead of half an hour, all directions, we need to be focused for 4 or 5 minutes (if there’s no enchō) in only one direction: the front (which is kind of natural, isn’t it? Considering our eyes always face the front anyway). And even doing this is sometimes difficult for some people.

Because of the pocket technology (we have the internet at the tips of our fingers 24/7), our attention span is so short that 5 minutes seems an eternity, doesn’t it? How to do it then? It is a true challange for the modern kendoka. Nowadays kendo is a martial art (sport/hobby only for some) and no longer a training method to go to a real fight. Do we have to go through a life and death situation to be able to keep focus? Of course not. The only way to keep focus is to demand it from oneself and consciously do it. It’s a lot easier to say this than doing it, but that is part of our training as kendoka.

This is why we train in kendo: we train our bodies to be strong and fast, we train our reactions to be accurate, we train our decisions to be final, not hesitant, and we train our minds to keep the focus.

What we do now is merely a representation of actually cutting. I’ve seen so many competitions where timing, determination and zanshin decided a hit to be scored as ippon (valid point), not the part of the bogu (armour) that was hit as we are taught in training. When sensei tell students that the hit must resemble a cut, students strive to do that without actually knowing how it is to know how making a cut feels. It’s quite difficult to be so far from the samurai era and to continue applying the principles they lived and died by. But I’m beside the point now.

The memories and observations of О̄dachi sensei hit deep. They made me think of the vanity of young kendoka (or the ones who have yet to settle their egos and search to better their own character instead of trying to go for a meaningless win in a end-of-training dojo keiko – fight). They think the older sensei are easy to score against, only to realize that when they face them that there’s no chance of winning. I think О̄dachi sensei’s background, being a fighter plane pilot in the WWII in the Special Attacks, is extremely special. That man was a mere teenager when he went to war, ready to die. He had to harden himself to stay alive and had to keep his focus sharp, his mind as calm as possible and reactions swift. Nothing else mattered apart from what happened then, in that very moment. Because that moment was decisive: would he live or would he die?

If we take the harsh reality of war and transfer it to modern kendo, what we are left with is understanding principles that we wear them as words on tenugui: fudōshin (不動心 – is a state of imperturbability, literally and metaphorically, “immovable mind” ) and mushin (無心, literally “no mind/empty mind”). During a kendo fight (or of anything else we do in this life), there should be no place in our minds for anything else than the thing we do. We should not waver, we should not hesitate. We should just focus on the present at hand.

This is the beauty and challange of kendo: teaching us principles that help people stay alive during wars in a time when such wars are not happening. This is truly the character polishing and body strengthening kendo is all about, in my opinion.

О̄dachi sensei will be 99 y.o. this year (not sure if he is still with us or passed away) and I find myself wishing I had at least witnessed one keiko he lead. If it wouldn’t be the language barrier, I truly believe that there are so many things to learn from him, not only about kendo, but also about life.

– Alice

P.S. for Romanian readers: s-ar putea să traduc acest articol în română la un moment dat. Însă până atunci, vă invit să îl citiți în engleză sau să folosiți funcția Google Translate pentru traducerea paginii în română. Mulțumesc de înțelegere.